Sculptural Paintings (2017-2018)

For my first sculptural painting, which I made in summer 2017, I envisioned two figures at opposite ends of the canvas, at once reaching towards each other and pulling each other apart. Moving away from direct figural representation, I created Twin Separation Anxiety by tearing, twisting, and knotting canvas, building tension before slathering it in paint. This new form allowed me to express bodily emotions and interpersonal relationships in a physical way.

I continued to explore this sculptural language at a larger scale in What are we going to do now?. The measurements of each side come from the height of each member of my family. The bottom is mom, the top is my dad, and the sides are the heights of me and my sister when we were twelve and a half - the age we were when he died. I poured months of physical and emotional labor into the piece, building up layers and layers of canvas and paint. Then I cut out the top support and waited for it all to collapse. But it didn’t collapse. It bent and buckled and took on new forms. The very process of grief that I set out to embody became a metaphor for resilience.

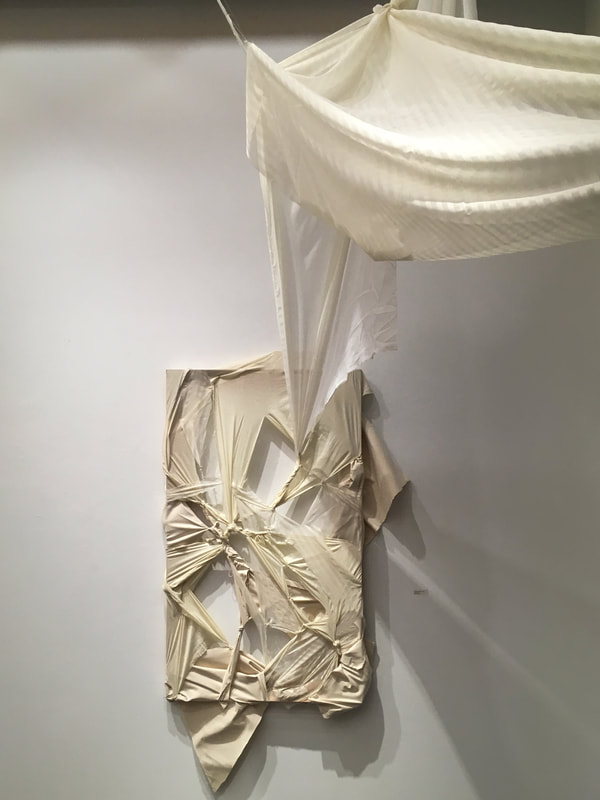

I returned to the piece a year later and remade it into a sculptural installation. My dad passed away many years ago, but it wasn’t until recently that my mom shared with me a dream she had had on the night that he died in the ICU. She dreamt that the stillborn twins that she had given birth to before my sister and I came down and took him away with them. This image of the twin angels played over and over again in my head. And so I rebuilt this body: heavy and sagging, but also lifted up by these twin strands of translucent fabric. I called it I don't know if I believe in angels. The tension that this piece holds as it is both pulled away and grounded led me to my textile work.

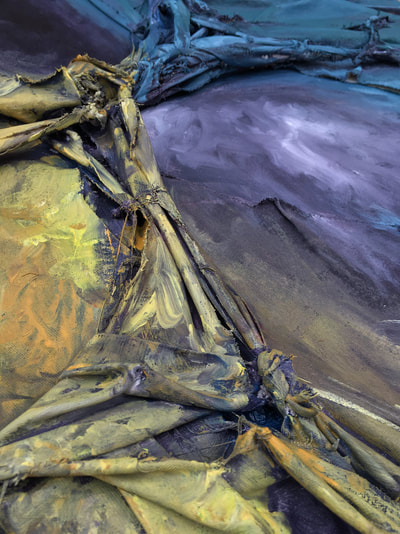

The final piece in this gallery, Tree of Life, is on view at Chashama Matawan Gallery (NJ) from August 13 to September 19, 2020. The exhibit, called Thoughts & Prayers, Another Round of Vacant Stares, examines gun violence and our country’s inability to respond to tragedy in a meaningful way. I made this piece on the evening after the Tree of Life synagogue shooting on October 27, 2018. For many Jewish communities across the country, including my own, the shooting sparked both grief over the lives that were tragically cut short, and also fear, that it so easily could have been our own synagogue targeted. Fear was accompanied by anger - that my non-Jewish peers seemed unaffected. After scattered condolences, their lives went on. This mixture of fear and outrage was only a fraction of what Black communities grapple with time and time again when Black people are murdered by white civilians and police. We can’t talk about gun violence without talking about police violence, and we can’t talk about police violence without talking about systemic racism.

Making this piece - stretching, twisting, and tearing fabrics, and then layering them back together into something new - became a way to process and take part in collective mourning. In Jewish mourning customs, there’s an ancient practice called 𝘒𝘳𝘪𝘢𝘩 that’s still observed today. Close relatives of a person who has died tear their clothing as a tangible symbol of their grief and anger in the face of loss. Symbolic and ritualistic practices can offer comfort to those impacted by tragedy. Beyond that, they can become tools of healing that rally us to fight for a safer and more equitable future. But we must not let them placate us - to numb our rage so that we stay quiet until the next tragedy erupts. Short-term consolation must lead to collective action, in order to bring about long-term healing and change.

I continued to explore this sculptural language at a larger scale in What are we going to do now?. The measurements of each side come from the height of each member of my family. The bottom is mom, the top is my dad, and the sides are the heights of me and my sister when we were twelve and a half - the age we were when he died. I poured months of physical and emotional labor into the piece, building up layers and layers of canvas and paint. Then I cut out the top support and waited for it all to collapse. But it didn’t collapse. It bent and buckled and took on new forms. The very process of grief that I set out to embody became a metaphor for resilience.

I returned to the piece a year later and remade it into a sculptural installation. My dad passed away many years ago, but it wasn’t until recently that my mom shared with me a dream she had had on the night that he died in the ICU. She dreamt that the stillborn twins that she had given birth to before my sister and I came down and took him away with them. This image of the twin angels played over and over again in my head. And so I rebuilt this body: heavy and sagging, but also lifted up by these twin strands of translucent fabric. I called it I don't know if I believe in angels. The tension that this piece holds as it is both pulled away and grounded led me to my textile work.

The final piece in this gallery, Tree of Life, is on view at Chashama Matawan Gallery (NJ) from August 13 to September 19, 2020. The exhibit, called Thoughts & Prayers, Another Round of Vacant Stares, examines gun violence and our country’s inability to respond to tragedy in a meaningful way. I made this piece on the evening after the Tree of Life synagogue shooting on October 27, 2018. For many Jewish communities across the country, including my own, the shooting sparked both grief over the lives that were tragically cut short, and also fear, that it so easily could have been our own synagogue targeted. Fear was accompanied by anger - that my non-Jewish peers seemed unaffected. After scattered condolences, their lives went on. This mixture of fear and outrage was only a fraction of what Black communities grapple with time and time again when Black people are murdered by white civilians and police. We can’t talk about gun violence without talking about police violence, and we can’t talk about police violence without talking about systemic racism.

Making this piece - stretching, twisting, and tearing fabrics, and then layering them back together into something new - became a way to process and take part in collective mourning. In Jewish mourning customs, there’s an ancient practice called 𝘒𝘳𝘪𝘢𝘩 that’s still observed today. Close relatives of a person who has died tear their clothing as a tangible symbol of their grief and anger in the face of loss. Symbolic and ritualistic practices can offer comfort to those impacted by tragedy. Beyond that, they can become tools of healing that rally us to fight for a safer and more equitable future. But we must not let them placate us - to numb our rage so that we stay quiet until the next tragedy erupts. Short-term consolation must lead to collective action, in order to bring about long-term healing and change.